Surgery, Swedish style

I have no insights to offer at the

moment, so instead I offer a play-by-play of my mastectomy and axillary dissection experience for those interested in

the lurid details.

Last Tuesday I got up at 3:45am (in itself a feat for me) and took my second “surgical shower:” you wash according

to your regular habits; turn the water off; wash yourself from the neck

down with a non-lathering surgical soap (active ingredient: chlorhexidine

gluconate); turn the water on; rinse. You do this before bed and again in

the morning before surgery. It’s a loathsome process but I’m grateful Swedish

is so anal in their anti-infection procedures.

I couldn’t eat or drink before surgery, couldn’t put on any

lotion or make-up or jewelry, have no hair to arrange, and my clothes would soon be

exchanged for scrubs, so there wasn’t much to think about before leaving the

house. Except food, but I’m obsessed with food so I did my thinking in advance.

I’d packed homemade granola and a box of

almond milk, unsweetened dried mangoes, homemade red lentil

soup, homemade gingered chicken meatball soup, homemade spiced almonds, smoked salmon, two apples, a pear, tea,

and a bar of dark chocolate from Layla.

I left the house at 4:15 a.m. and drove to the ferry, which

I then lazily drove onto with a handful of other drivers and a few seriously

hard-core bicycle commuters. (Bainbridge bicycle-ferry commuters are The Bomb.

The hills on this island are not for sissies.) I reclined the seat and

semi-snoozed across Puget Sound. Have I mentioned how much I love ferry commuting?

On the other side, I drove to Swedish, parked, locked my ridiculous

food cache in the car and arrived at registration at 5:30 a.m. as instructed.

My dad showed up an hour later to babysit my street clothes and make sure the

doctors looked legit, and by 7:30 a.m. I was in the operating room inhaling my

last breaths of consciousness and hoping the surgeon wasn’t as tired as I was.

He held my hand as the gas mask went on my face, a gesture I found chivalrous

and humanizing.

A few moments or hours later, the bleary colors and sounds

of the recovery room enveloped me. People in green bent over me and spoke; I spoke back. More green people wheeled me around on my gurney, down

hallways and into elevators and down more hallways until I was transferred to a

bed in room 305. Brian and my dad appeared, as did a nurse named Kerri.

Kerri reminded me of someone I know and like, though I can’t

place who. By the time two days was over, I was lobbying her to do a locum tenens stint in Juneau. All signs

point to failure; apparently she really likes her home, her part-time schedule,

her volunteer work, and her husband. Kerri and I talked a lot. Frighteningly

enough, I can’t remember everything I told her, and I suspect I mistook the

poor woman for my best friend, therapist and sister all in one. For her part, she

valiantly tended to my drain (more on that later), measured my urinary output (she

declared that I have a nurse’s bladder; I told her my obsessive fluid intake during

chemo stretched my bladder), and pretended to be interested in pictures of my

children.

On surgery day, I had three goals. Or I should say, my

medical team had three goals for me. Written on a white board on my hospital

room wall, under the preprinted heading “Goals for today,” was the following:

Pain management

Urinate

Walk in hall

Being goal-oriented, I accomplished these with reasonable

ease and went to sleep feeling I’d done a good day’s work.

The night was tolerable, given that I had to sleep at a 30

degree angle so gravity would pull blood and lymph in the right direction. The

night nurse, Mercy, was quiet and gentle. Nonetheless, I was awakened four

times: twice by Mercy for vitals, once by a young bearded apparition who claimed

he was a surgical nurse and needed to check my drain site, and once by a woman

who said she was a surgeon and wanted to see if I had any questions. I did not.

Just about everyone asked, day and night, if I wanted drugs. I did not.

My surgeon visited in the morning. He enthusiastically

pressed on my bandages to move fluids toward the drain tube. I will only say

this was not pleasant. Even Kerri winced.

I ate exactly none of the carefully prepared foods I brought.

In the end, the thrill of picking up an old-school corded phone and pressing

55555 to access all the free a-la-carte food I might possibly want overwhelmed my

purist pretenses. Besides, what else is there to do in the hospital but get

excited about the pending delivery of Seasonal Fresh Fruit Cup, Mediterranean

Plate, Oven Roasted Red Potatoes and Bistro Salad? Hospital food has come a

long way, baby.

Having fled the hospital the same day when I delivered Alder

(residual trauma from a high-decibel night nurse after Rosie’s birth), only to

regret my hasty return to dishes and a child and to-do lists, last Wednesday I

dawdled at the hospital. My father was on Bainbridge and had brought a zillion-piece

Lego City mining set that would occupy Alder for the rest of the millenium. No need to feel

guilty, right? So I did more hall walking with Brian, more chatting with Kerri,

more getting-trounced-at-rummy, and more a-la-carte ordering. Finally around 2 p.m.,

we said goodbye and left.

At least, we tried to leave. There was the slight problem of

a dead car battery. Once we solved that problem with the aid of Carl from

Maintenance, we went to Bartell’s Drugs, as I had signed up to send candy to

school with Alder on Halloween for a class cookie-decorating project – yes, his

school is surprisingly mellow about refined sugar and food sharing. Although I’m not a big fan of either, I find it

endearing that the school is so blithely last-century about these things.

The past week has been largely dominated by the aforementioned

drain. WARNING: If you are squeamish, skip the next paragraph.

The drain is a clear plastic tube about 8 mm in diameter that

relieves blood and lymph that might otherwise cause a fluid build-up. The drain

begins under the skin. It wends its way around the area that used to be my

breast and emerges from a hole under my armpit, where it is sutured in place.

At the other end is a grenade-shaped clear plastic bulb. It's not particularly comfortable. Every few hours, or at

least three times a day, we have to “strip the milk,” which means squeeze the fluid and clots down the tube into the grenade. We then measure and record volume,

and flush the contents down the toilet. Thankfully, this has been Brian’s job.

The drain remains until I produce under 30 cc’s of fluid a

day. Yesterday I got below 175 cc’s for the first time, but it’s looking like I’ll

have my little sidekick for a while yet.

One woman on a breast

cancer discussion board, who said she is HIV positive, wrote that she’s squeamish

and almost passed out reading a description of how the drains work. For some

reason the thought of this woman with cancer and HIV fainting over a drain made

me laugh so hard I cried. The humanity of it all.

****

I'm now done with two of three components of my slash-burn-and-poison cancer treatment regime (all that remains is burning, a.k.a. radiation). The infusion nurse at my final chemo treatment asked me out

of the blue, “How are you coping with the loss?”

I was momentarily flummoxed. “What loss?” I asked. It was

the week of the three-year anniversary of John’s death and two-year anniversary

of Ali’s death. What did it say about me on that monitor she’d been reading?

“Isn’t your surgery coming up?” she asked.

Oh, right. I was scheduled to lose my breast in 13 days. "It’s not that big a deal,” I said.

I seem to have a natural anesthetic when it comes to loss. Perhaps

we all do. It wears off over time, but I suppose it protects us when the pain

would be most acute, allowing us to function and laugh and begin to heal. Little

by little, we let in the loss as we are ready and as time and new gifts and new

strengths begin to soften the pain. Someday I may lament my missing breast,

but for now it’s just kind of a science project on my chest, one I hope

expunged the cancer from my body.

| At Walmart the Friday night before surgery. I am asking my friend Shona, "How did my life bring me here?" |

|

| Alder and Brian doing the pumpkin slinger at a nearby pumpkin patch. |

|

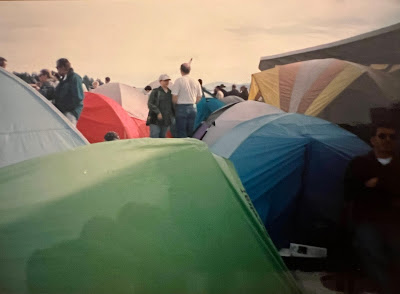

| Alder loves picking pumpkins, slinging pumpkins, carving pumpkins, making Halloween decorations, and decorating Halloween cookies. Just don't try to make him dress up. |

|

| Moments before Alder refused to go trick-or-treating. OK with me; I was two days post-op and dreading candy battles. |

Thank you for blogging your journey. I'm reading and sending you good vibes. Keep on running!

ReplyDeleteJamie B

Thanks, Jamie :)

DeleteThe running ain't happening for a while but I am motivated to rejoin my favorite running crew in the world, Juneau runners!